Maths and Ethics

For the last 10 school weeks, I’ve been running an EA-ish club at my high school, and it has been extremely fun. This is what we did week by week as best as I remember and kept track, and my thinking surrounding it.

General Thoughts and Fun Things

This is one of my highlights every week, talking about math and mathematical ethics with excited nerdy tweens and teens is such a blast, and these ideas are genuinely so interesting

After it coming up several times, they now remember that something like 10% of people live in absolute poverty, there are just a number of callbacks like that and we are creating a knowledge base together and it’s so great

Each week is sort of concept-based and sort of activity-based. There are a vast number of concepts that are some combination of useful for thinking clearly, at the intersection of maths and ethics, and interesting, and since I’m just trying to get them playing with the ideas here, it feels like there’s a ton of room to be creative with how I approach the topics.

Interactive stuff is usually way more fun and memorable (impactful? I don’t know) and I have so far felt like all of the concepts I want to talk about lend themselves really well to being interactive

I’m sort of obsessed with the “be grounded in how big numbers actually are” thing right now and it’s really fun to bring in here

I love getting to talk to each of them about their opinions and views and create a space where mostly there aren’t right answers and they get to have the views they have (which doesn’t mean I won’t push back!). Posing thought experiments and then asking each and every single person their view (just the answer, there of course isn’t time for each person’s explanation) has gone such a long way towards this, I believe.

It’s only 30 minutes every week and I always wish I had more time and it feels like there’s tons of fun things we could do

The thing I’m doing least of right now is pushing on depth or getting them to do much on their own. It’s a survey of interesting ideas. If I wanted depth, or research projects, I’d need:

To intentionally create more buy-in, more line in the sand moments where I say, ok, this is what being In looks like, if you want to be in, see you next week

They are curious and interested and I think would want to apply this kind of thing in their own life, but doing it formally isn’t a norm I’ve set

Perhaps as a result of the above, more consistency in who comes

More consistency myself

Possibly older students

That said, I think the fun stuff could very easily lay the groundwork. At the end of 75% of a school year on this, I think I could absolutely ask them what they wanted to do to proceed, whether they wanted recommendations of books, podcasts, videos, or to create a project

The name and framing

I didn’t want to call it “Effective Altruism” because I didn’t think people would know what that was, and it felt like a big commitment to a big set of ideas that I wasn’t yet sure how to convey, discuss or communicate with younger people (the club was open to all from Year 7 - 13 / Grade 6 - 12). I wanted the freedom to make it less about morality and more about interesting ideas, questions and techniques, and I’m a math(s) teacher, so I thought it would seem squarely in my wheelhouse.

An unexpected benefit of this framing is that 1. a bunch of math nerds showed up, and I <3 them, and 2. I felt way more able to actually just do math on the whiteboard when relevant instead of worrying I was boring them or turning people off.

Plus, I find it a very charming framing.

How to begin?

I thought a bunch about what to start with. The core generator I wanted to use was “what’s a useful and interesting intellectual idea”, but everything felt so connected to everything else that I found it hard to pick apart one. In the end I went with expected value which hit a bunch of features

Very basic mathematically, but one most would not have seen

It’s more mathsy than it is ethicsy

Transportable to lots of other contexts

Really useful in future discussions, though I didn’t realize this fully at the time

We could talk about betting

So I made this poster to put around the school and have the text of read out at an assembly. The refugee campaign was a reference to a donation opportunity that had come up a lot in the school’s assemblies in previous weeks.

Week 1: Expected Value

Unsurprisingly, I spent the most time planning out this week. I had a whole lesson plan, which you can find here.

I wanted to start by talking about how there are a lot of pressing problems in the world, and how time and money and knowledge are scarce, leading to “how do we prioritize” and I wanted to hear from them what they thought we should do about it.

I was ready to ask them which is more important to fix: poverty or baldness? and then press them on why - baldness really bothers those afflicted and affects a lot of people! I wanted to push that there was compassion available for all kinds of suffering, and some decisions weren’t the least bit obvious.

We talked about the framing question of the event, running the campaign versus giving the money.

Considerations we generated together

How many people we can affect

Our estimates of how likely we'd be to succeed in the campaign

In some sense, everything is a bet. Coming to the club meeting is a bet on how much it will feel worth your time.

We talked about what probabilities of success would sway us and why they mattered.

How much we can help the people we affect

How bad the problem they're facing is

Games / Thought Experiments

I printed these and asked each person their view. I had only a couple attendees the first time, so this was easy but in general I have kept to asking every single person their view on each question like this and I think it has really contributed to a feeling that everyone’s view matters, that there are often not right answers, and that I care what they have to say.

Would you take #1:

A sure £5

£12 if a coin comes up heads?

What if you were picking one to do a billion times? Does your answer change? Why?

Would you take #2:

I flip a coin and pay you ten pounds if it comes up heads. How much would you pay to play? How many times would you pay?

Would you take #3:

Should you play the lottery? Why or why not? When or when not?

Would you take #4:

A 5% chance at £1,000,000,000

A sure £10,000,000?

Expected Value

I taught how to calculate expected value, and framed it as what we’d expect on average, and talked a bunch about what we’d do if we got to play a billion times versus once. We talked about the weirdness of wanting to make different decisions in those cases, but that for one participant that desire was there, and the certainty she was purchasing, and what probability would sway her. I also described expected value as in some sense what the game is “worth” to play.

I also liked asking “how much would you pay to play the ‘$10 for a head on a coin flip’ game” since it really gave them full agency.

Framing Effects

With two attendees, one got a paper that said:

600 people are affected by a deadly disease:

Which treatment do you administer?

Treatment A: Will save 200 lives

Treatment B: Has a 1/3 chance of saving all 600 people, and a 2/3 chance of saving no one.

And the other a paper that said:

600 people are affected by a deadly disease:

Which treatment do you administer?

Treatment A: 400 people will die

Treatment B: Has a 1/3 chance that no one dies, and a 2/3 chance that all 600 will die.

I had them answer, then switch. Then we talked about the expected value and how that did or didn’t affect our decision. Then the fun part, where I pointed out that these are the same. This is from the famous Kahneman and Tversky study, and it really hit one student hard.

Takeaway: People are going to try to convince you of all kinds of things, and doing the maths can help you not get swayed by differences just in how things are phrased.

Overall, expected value was framed as a mathematical input into our decision, not a requirement, and that if other things mattered to us we could bring them into the maths as well.

How’d it go? I think well, though there were just the two students. They were curious and one kept coming back. I forget if the other had scheduling issues or wasn’t as interested. It was maybe maths-heavy, but I also think that set a tone. (That said, the overlap wasn’t that large in the set of people coming in the first few, so it may or may not have mattered.) Nonetheless, I think they had some illuminating moments and felt like they got taught something concrete.

Week 2: How much is money worth? (Marginal utility)

I wanted to play with keeping the framing and adapting the story, so the advertising I sent around asked:

“If you had £1,000,000 to give away to refugees, would you: split it among 10 people? 20 people? 50? 1,000,000? How would you decide?”

I liked that this kept the original hypothetical, picked “give it to them” but then dug in on that. There are complexities all the way down!

The goal was to get at decreasing marginal value of money and the tradeoffs therein. I intended to follow up by talking about the research on logarithmic utility in income (and the weaknesses of it) and asking them to get at their own intuitions with it, but we ended up having too much fun talking about what money and time were worth to us.

I asked them how much they’d need to be paid to do half an hour of marking (grading) for me, and they all gave me their prices, and I pushed them on “so that’s what your time is worth”, only to then ask how long they’d do it for. The fact that it was finite pointed to their fifth half an hour was worth something different to them than their first, which seemed genuinely novel to them. (Had a few more students this time, mostly around age 13)

Takeaway: Figure out what you’d charge for something to get a sense of what it’s worth to you

How’d it go? This was really fun and engaging, as evidenced by the fact that I went off topic and got to really push them on what their time was worth to them and what that meant. This also set me up to be able to refer to it later.

Week 3: What can you buy for money?

I went into this week thinking that I’d finally get to the logarithmic utility question but instead we talked about how much money really rich people have. One student said they’d heard that if we took all the billionaires’ money, we could end poverty.

In perhaps my favorite moment of the whole club, I was like, ok, let’s look it up. And we spent a while looking at billionaires’ net worth, and I was like, “oh, Larry Page has 91.5 billion, Sergey Brin has 89 billion, makes sense they’re so close, they founded google together” and they nodded and then I was like “the difference between them is 2.5 BILLION DOLLARS!!!” and we talked about big numbers and remembering what the number actually represents and how much money that is.

We added up the top ten richest people’s money and divided it by the number of people in the world with wolfram alpha (teaching them about wolfram alpha might be the most valuable thing I do for them, tbh), which gets you $149. Once, not annually, since this is net worth. They pointed out that maybe we should only give the money to the poorest. So I had them guess what percent of the world lives on less than $1.90 a day. We had a range of guesses, looked it up and got 9%. Did the division that way and got $1660 per person. I asked them if that solved poverty. (And also pointed out that to a person on $1.90 a day, that was 2-3 years of income. It is not trivial). I think when we did it, we actually did the math if you left each billionaire a billion dollars, to be nice.

That seemed eye opening to them. I hope I imparted the “just look it up” message, which came up again and again from then on. They were amusingly happy to take these ten people’s wealth in toto because, you know, they’re rich, despite that I think most students at this school come from very wealthy backgrounds themselves.

In fact, I had them guess in what percentile their family was for world wealth, and they were quite off, as you might imagine. I didn’t have anyone say anything about their family’s actual finances except their guess, and put an average teacher’s salary into Giving What We Can’s calculator, and pushed them just a bit on the cavalierness towards the billionaires relative to where they might be in the distribution. I talked about how privileged I personally felt as a result of these percentiles but didn’t make a big thing of it.

On a whim, decided to look at global distribution of wealth, bringing us to this graph, and I pushed them to tell me what the graph was of (another time that the name Maths and Ethics came in handy). Also meant I got to plug Our World in Data.

It was cool to talk about the world getting more equal and richer and lots of people getting out of absolute poverty in just ten years, but also, where are we on that graph? And I made a big show of walking off the side of the screen and pointing to a spot on the board on the far right. The right end of the graph doesn’t even get close to median income in the UK.

Takeaways: Look stuff up, big numbers are big, we are globally rich.

How’d it go? I really enjoyed this one, but I think it maybe stuck with them least or second least of the concepts? At least, it feels like it basically hasn’t come up since. Maybe too moralizing or makes them feel weird about wealth? Though it’s very common at schools like this in my experience to talk about privilege, so I’m not sure this is so different.

Week 4: Happiness and Income

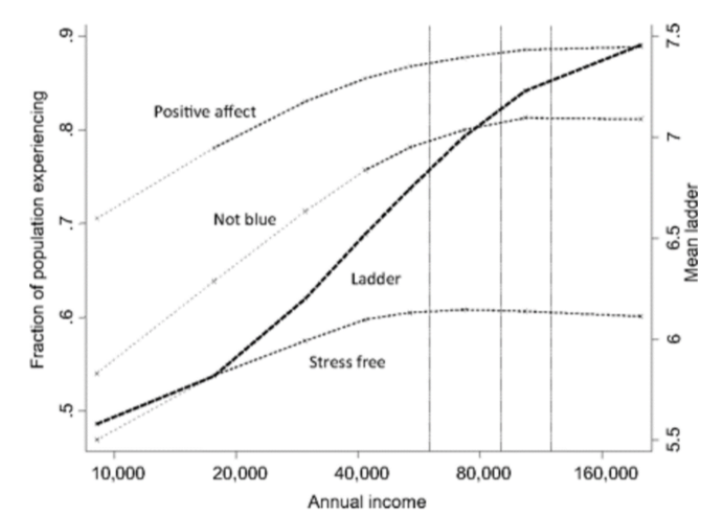

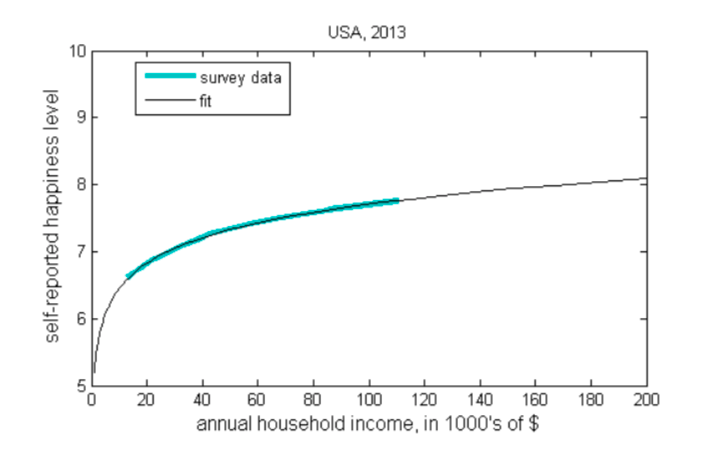

It finally happened. I printed the sheets here and had them all fill out their personal graph of how happy they thought they would be at various incomes on a made-up ten point scale. This is an amazingly janky table I made by taking one from a paper on income and happiness, taking out the data and replacing the dollar sign with a pound sign in I think MS paint.

Then I had everyone draw their graph on the board just to see it all at once (I didn’t force them but did ask), and we talked about it. One student said they’d donate everything above a certain amount, because “who needed that much.” Some students said they didn’t even know what they’d spend the money on (which I pushed back on, in that probably with some creativity you could find something excellent to do with it, some billionaires try to do cool things). It was fun to see their individual thoughts about it!

We talked about how the scale can go way further to the right, lots of people make more money than that, and how often people’s graphs are convex, and why.

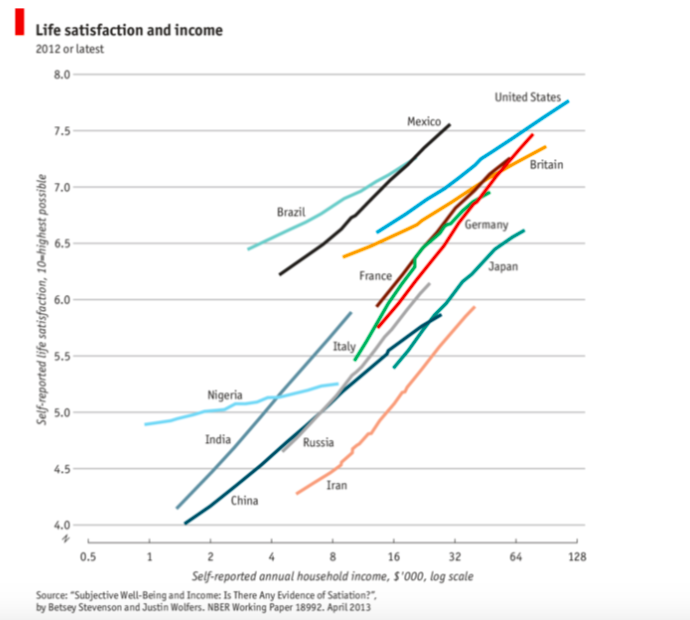

Then I showed them graphs of happiness vs. income, and that convexity and when it does and doesn’t appear.

Then I challenged them on the third graph.

Why do some of the lines not overlap at all on the x axis?

(Some countries are much poorer than others)

Why are they straight lines when none of the rest are?

Took some prompting, but they eventually realized that the x axis was doubling instead of increasing linearly (many of the students were year 9s, who had just recently done linear growth! It was perfect).

I had them redo their graphs on a second blank I had provided, after changing the x axis to be a doubling

Left them knowing that this was a log scale, I believe, and we talked about why that might be useful

Fit more data on an axis

Sometimes doubling matters more than increasing by the same amount (like you notice 10% increase in weight, not 2 kilos no matter what, according to a study I heard about once). I think this was not super intuitive to them and it would be cool to set up more thought experiments and real experiments (like with weight or perception of numbers) to make this visceral

The big moment was my offhand comment at the end, that this was a mathematical reason that could justify donating to those who have less, that this encodes our intuitions (I don’t know if I made the point this way) that the same money does a lot more for people who have less than it does for us. This seemed to really hit home, so I told them that the next time we’d talk about donations.

How’d it go? This one hasn’t come up very much since, but I’m really happy that they now all have these graphs they’ve made. I have a theory that I haven’t tested that leaving people who come to talks/workshops/club meetings/events with a thing they’ve made: an argument written up, a next step planned out, a graph, a something makes it feel real and productive and gives them something to remember the event by and look back on once they’ve developed their thinking more.

Week 5: Effective and Ineffective Donation

This week was my most standard EA introduction week, and I think wasn’t as amazing and fun as the others, mostly because it was a more empirical, less conceptual set of topics, and because it was more aimed at a goal instead of going where the winds took me. I think I could have done this better.

But still fun! I told them the story of PlayPumps, and good intentions not being enough. They asked good questions about “how could they not have known” and we skimmed this post to find answers.

We talked about guide dogs vs. trachoma surgeries, which I think didn’t land super hard but was a good conversation, and they were shocked at how much guide dogs take to raise.

The best part, I think, was doing a cost effectiveness analysis ourselves. I asked them for a worthy cause, and they said the Trevor Project, and we went through making estimates of, given a certain donation, maybe £1000, how many people could be employed, and how many people would be helped by those people, and how many points the helped people would increase on the silly made-up ten point scale from last week, and aggregated everyone’s estimates into a range of happiness points per £. Discussing and debating all the estimates was really fun and gave a sense of all the complexities and the value of taking averages and getting to use expected value.

Takeaway: I told them that while this obviously didn’t tell us everything, it was an exercise you could go through for different ways of doing good and see what happened

How’d it go? They were really engaged in the discussion of what numbers we should put on all the considerations, and I was really gratified to see that no one seemed hurt or offended or scared to express their view, even when others differed (as far as I could tell, of course). They were also quite willing to go along with the “silly ten point happiness scale”, which was useful for the activity, and made it helpful that we had done the previous exercise with it. I don’t think it really left them with a deep sense of why it matters, the big deal about comparing these things, and I’d want to tread lightly pushing on that, so it’s possible this doesn’t really make sense if I’m not going to go all in with it.

Week 6 (Term II, Week 1): Calibration

It was a new term, so I decided the theme would be prediction, calibration and forecasting. My messaging:

Maths and Ethics is back! Join us in this term to talk about big numbers and ethics, prediction and the future, and how well you know the world.

How accurate are you? How well calibrated are you? Try the questions below.

This iteration had the most attendance yet, not even including that there were three primary school students visiting on a taster day.

I showed Vox’s 2021 predictions and had the students figure out what the number after each statement meant.

I asked them if they knew the kind of people who were annoyingly always right about things, or who sounded really confident about things but were often wrong, which was a fun route into the value of being calibrated (you don’t want to be the latter person, do you??). We also had a fun conversation on underconfidence and overconfidence (there was a feminism angle here, too, I teach at an all girls’ school).

We talked about how nice it would be to be able to look at someone’s track record, to know who to trust, which led to me putting something like (but better in the moment, I think) these definitions of inside view and outside view on the board

Inside view: What you think because of things specific to the issue

Outside view: What you think because of how things like this tend to go

And we talked about how nice it would be to personally be more consistently right about things, or at least well-calibrated.

As many people do, they think overconfidence is bad and underconfidence is fine.

I tried to pitch them on the value of being actually calibrated, actually in touch with the world, that “arrogance” and so on are social words, but there’s a real reality back there we’re trying to figure out.

My next point (which tied in with feminism) was that if they are underconfident they will leave decisions and conversations to be dominated by people who are overconfident.

The next week I brought up that 0.1% chance of aliens sounds less confident than 1% chance but they correspond to 99.9% chance of no aliens vs 99%

Entropy and information theory for another day :)

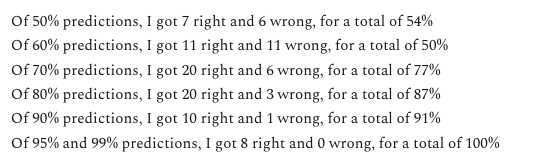

We looked at Scott’s calibration graph and I didn’t explain it at all. They got the two pictures below and told me what was going on.

So then it was time to test their calibration! I shouted out questions from the Scout Mindset Calibration Tool created by @adrusi and had them write their answers and confidence on whiteboards (good opportunity to ask why <50% confident wasn’t an option). I gave anyone who said 100% a very (teasingly) hard time - telling them that that meant they’d be willing to promise me a billion pounds if they were wrong. In future I will use their phone or something much more concrete and near mode as an example.

Then I showed the right answers and for time constraints asked them to eyeball their calibration. So fun to watch students proud of themselves for getting 45% of a set of questions right because it was reasonably well calibrated! And fun to (teasingly) shame students who got any questions they put 100% confidence on wrong (100% wasn’t even one of the scout mindset options!!).

Extremely fun, do recommend.

How’d it go? Great! I think they really engaged with the over/underconfidence question, felt like it applied to their lives, and were shockingly willing to be put to the test. I hope I successfully conveyed (and I will continue to emphasize it, especially if we do forecasting and superforecasting) that this is a skill and one you can improve at by doing exercises like this.

My post in the group Teams after

We looked at people who made predictions: A blogger named Scott Alexander does this every year, here are his 2021 predictions and here's how they went. The news site Vox does as well, here are their 2021 predictions and here's how they went and here are their 2022 predictions. Do you agree or disagree? We talked about overconfidence, underconfidence and being well calibrated.

So we practiced calibration, and you can continue the quiz on your own and post your calibration below: https://calibration-practice.neocities.org/. More quizzes and some lovely explanation available here: https://www.clearerthinking.org/post/2019/10/16/practice-making-accurate-predictions-with-our-new-tool

Week 7 (Term II, Week 2): Predictions

This was the week before half-term break (a week long break in February, which I am on right now!) so we talked a bit more about predictions. We talked about how to figure out who’s right, and one student volunteered that she makes bets with her sister (paid in chocolate) when they disagree about what will happen, which was a brilliant segue into prediction markets. I showed predictit and how it works, and we talked about when the cost of the ticket corresponds to the probability by doing an expected value calculation, which was also good since the students there hadn’t been at the very first session. Having a d12 on me helped me re-introduce the topic, since I could just say it cost £1 to roll the die and asked how much they’d need to make on rolling a winning 1 for it to be worth playing.

Then I just had them make as many as they could (I think at least 5) about what would be true in two weeks (when I see them next) and then if they had time about things in a year, plus credences. Low-key, and I collected their predictions to hand back next time. I will likely briefly show metaculus and less briefly show prediction book as a way to log their predictions for things that will happen far in the future, showing their track record.

How’d it go? Good but not great. I think the idea is good, but I needed to give them more examples of the kinds of things they could predict about their lives and the world, since I think they struggled with that, and it made the whole thing take longer and feel a bit rushed. When we checked in on their predictions after break, they didn’t have enough to check calibration.

Week 8: Fermi Problems

They came back from break, checked their predictions, but didn’t have enough to really check for calibration, and none of it had the punch of “woah, that’s what I expected??” that I expected.

I decided to do Fermi problems. I gave them the choice of

How many google searches happen a day

What percent of words in google books is X (where X is to be decided together)

How many people could exist in the future? (Baiting for a big conversation on that, but they didn’t bite)

Other things I don’t remember

I like the idea of doing “how many calories would we need to feed everyone for a year?” and in general asking questions with intrinsically wild answers that have radical implications all on their own, but Fermi questions are just great by themselves.

They picked google searches, and I walked them through thinking about how to build up a model out of random things they think: what’s the average number of google searches per person? How many people google things a day? We ended up an order of magnitude off (and I emphasized that order of magnitude correctness is the win condition).

I then sent them to the whiteboards to figure out what percent of words in books (according to google’s ngrams) are the word “animal.” This was great! Some of them brought up concerns about which words get into google books, some of them opened up the books nearest them to count how many times the word animal appeared on an average page and then used the number of pages in a book. Some got the right order of magnitude! Some didn’t, but I loved seeing them work through it.

Resources thoughts:

I really like the Less Wrong introduction to Fermi problems, their history and how to do them.

I found it surprisingly hard to get a good list of just a ton of potential problems where the answer is look-uppable, and are interesting (not just how many balls would fit in this room, as fun as that is.) I’ve collated a set of resources I did find here.

I’d like to make more use of xkcd’s What If column. Had an amazing win many years ago when I offered students the chance to make their own and one calculated the number of ants in Pennsylvania, but it broadly doesn’t have the appeal I keep imagining it will in the 2-3 times I’ve talked about it in classrooms.

I love this site of estimation opportunities, where you have to guess / figure out how tall something is or how many cheese balls will fit on the plate or whatever based on the picture or video shown.

How’d it go? Really well. Fun, engaging, interactive, gave them a chance to think and gave them a sense of the skill quite quickly. If I recall correctly, they wanted to do more than we had time for. In general, I think things with answers are pretty motivating in a way that unanswerable questions sometimes aren’t (but it varies a lot, cf “doors vs. cars”).

Week 9: What does randomness look like?

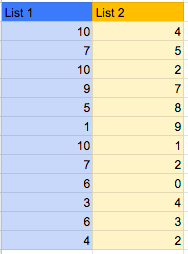

The students had expressed interest in doing more Fermi problems but when I suggested it they looked not that interested (and I got the impression were sort of just happy to do whatever I brought to the table), so I improvised from the very list below of topics that might be good to do I hadn’t done yet and picked “what does randomness look like”. I quickly made a spreadsheet like this where they had to figure out which list was random and which wasn’t.

Similarly, I showed them random points and emphasized the difference with uniform points and that people get this wrong.

I tried to talk intelligently about the patterns that appear when people try to fake numbers, like making some digits random when they actually have an empirical distribution, and Benford’s Law, but didn’t know it well enough to really do a good job. One of the students asked a good question out of her confusion and she was right that my explanation as it was didn’t make sense, so good on her! I was trying to riff off my recollection of learning this on an intuitive level from the criminally unknown Conned Again, Watson when I was young, but would have needed to prepare better.

How’d it go? It was actually pretty good despite clearly potentially going much better if I’d known what I was talking about. I think they came away with “randomness isn’t uniformity and your intuitions around randomness are maybe very bad.” The counterintuitiveness is gripping, and the “catch fraudsters” angle is fun as well.

Week 10: Population Ethics

I find the question “should we make people happy or happy people?” so gripping per words used (the cleverness of the construction helps a lot), so I wanted to present them with that, and then do the repugnant conclusion and then talk about it, but they had some unexpectedly skeptical views on how good happiness is or perhaps how realistic it is and seemed resistant to fully engaging with the hypothetical of “creating a happy person”, so we just talked about life and happiness. Didn’t seem worth going with “this obviously true assumption might lead you down unexpected paths!” when the assumption wasn’t obviously true to them.

How’d it go? Unexpected total failure of original goal, lovely to just hear and connect with them. Might be a general thing with Gen Z people who have some doomer-y elements in their zeitgeist. I would have thought it had to do with being less interested in philosophy but I know that some of them are. They are on the young side, which I think made “take hypotheticals seriously” less easy to make happen in general. Shame not to get to dig into some philosophy. Maybe a point for “object level and maths” over philosophy, since they more clearly have answers, which makes them more motivating to think about?

Week 11: Problems are for Solving

Did a sort of basic rationality debugging session, asking questions like / saying things like:

How long does that take you normally?

What’s a concrete plan for that? How will you remember?

It’s ok to do slightly weird things if they work for you

Can you concretely visualize the steps in the thing you have to do?

When are you most likely to actually be able to get this done?

Can you be curious about why you don’t do the thing you’re trying?

It’s worth trying out a bunch of approaches to productivity / your emotions around work since it’s important and you’re young and in Explore mode

How’d it go? Very fun, fast paced. They really liked it and I think it was a good intro to that way of being. I followed up the next week and one person reported feeling like some problems had been solved but no one who had a pile of work or aversions to writing English essays felt any progress had been made there, not so surprisingly, so not very directly impactful!

End

I had my last meeting with them and thought through some books that had been influential for me in thinking in rationalist ways before I found rationality. The ones that primarily came to mind were

Conned Again, Watson, a Sherlock Holmes themed set of math and probability puzzles which is excellent and contains a discussion of what true randomness looks like versus faked randomness in addition to a great description (in my recollection) of the Monty Hall problem.

The Pig Who Wants to Be Eaten, a collection of philosophical thought experiments that felt so gripping and like brain crack that I wrote some college admissions essays about thought experiments.

Potential Ideas for the future

Fully babble, feel free to steal, add, etc.

Bayes and probability puzzles

Julia Galef’s great video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BrK7X_XlGB8

Foxes and hedgehogs

Which do they think they are? What do they like about it? What do they like about the other way of doing it?

What are ways of cultivating the virtues they want more of?

Grand futures. What do you think would happen? What would be good if it happened?

What science fiction do they like? What do they find inspiring?

Can we create a vision of something we’d be excited to see?

Maybe introduction to longtermism as an interesting thing people think about

Making models with spreadsheets and guesstimate

More population ethics

Impossibility theorems are always fun

Play with thought experiments and counterintuitivity

Different kinds of distributions and power laws

I bet it will be so fun to look at Zipf’s law in corpuses and talk about why it happens

Guess what height distribution looks like, look at it, say that this is what happens when you add independent things

Can talk about overlapping bell curves for things like gender

Find examples of log normality, talk about when that happens

I like Spencer Greenberg’s list of distributions and descriptions and when to expect different ones

What randomness actually looks like

Why we should expect clumps and nonuniformity, there’s good stuff in Conned Again, Watson where you look at two sets of birthdays and two sets of random dots and guess which is actually random

Benford’s law, how people catch cheaters

Statistics: Use r psychologist’s beautiful interactive visualizations to talk about how we know things like medical treatments work, when we should expect things to happen by chance, cohen’s d in an intuitive way, things like that

Big things to solve in the world, let’s make a list?

There’s some really interesting stuff! AI, space governance!

Rank them in different ways?

Make a shared spreadsheet

Career thoughts? How do you want to think about it? What would be helpful to them?

NTI framework - comes naturally out of conversations we’ve already had

Some rationality training - lines of retreat, resolve cycles

Noticing

Buy them cheap knitting counters and tell them to pick something to Notice and count it over the course of the week - maybe do smells all together the first time

https://www.loganstrohl.com/nature-study

Other??